Shipping country

Wood Species

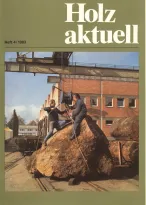

Burls: highly coveted whims of nature!

An article from a 1985 publication of the Danzer veneer company has lost none of its fascination almost 40 years after its appearance: large burls are still among the most valuable woods in the international trade.

The huge tubers and burls depicted in the photographs certainly represent rather unique one-off specimens found only every -ty years, and in this respect this article represents a rare source of images of one-off rarities from a long period of the second half of the 20th century.

The article of the eminent scientist, researcher and author Helmut Gottwald (1918 -2008) represents an important source on the subject of measles growth, the contents of which are unique in this concentration precisely because of the unique images. Here are excerpts from the text by Prof. Gottwald as well as some pictures of sensational rarities from Danzer Veneers.

Burl growth: a picturesque freak of nature! by Helmut Gottwald, Reinbek

Burl woods are among the most decorative woods on earth due to their structural appearance. There are not many of them, because their species and growth areas are limited, and only a limited number are on the market. They come from deciduous and coniferous trees, whose wood, caused by a budding occurring in a clustered form, has extraordinary structures.

The following article provides an overview of the most important species as well as the origin and characteristics of burl growth.

Since the production of furniture and parts for interior finishing has increasingly been based not only on technical requirements but also on appearance, the choice of wood species has increasingly been determined by the appearance of the wood. Already in historical times it was the desire of the privileged classes to own beautiful or fancy pieces of furniture, which, in addition to their usefulness, also pleased by the beauty of the material. This is how furniture came into being, which, due to a deliberately sought after imagery of wood and the wealth of ideas in the composition of material and form, are among the essential elements in the development of our living culture.

The decisive aesthetic and economic aspects of using the material wood in all its natural diversity also led to the use of unusual and often only sporadically occurring growth forms of generally known wood species, such as bar growth in maple or the 'pyramid' and 'pommelé' structures in mahogany woods, for an additional expansion of the aesthetic expressiveness of the wood. It is understandable that such individually structured woods for special pieces of furniture and decorative room furnishings were sought after at all times and still enjoy high esteem today across all fashions.

One of the most striking deviations from the normal wood structure is the grain growth: it is a wood with numerous fine, swirly structures.

One of the most striking deviations from the normal structure of wood is probably burl growth: it is a conspicuous grain pattern with numerous fine, swirly structures, caused by an accumulation of buds or very fine knots over many years, the causes of which have not yet been definitively clarified. This picturesque whim of nature has always aroused the special interest of wood processors. Thus, already the Roman writer Pliny the Elder, who dealt with nature in detail in his writings in the middle of the first century AD, gave a description of burl growth. Already in his time Thuja burl was used for decorative design of furniture and utensils. During the Middle Ages, the use of thin-cut wood with a mostly unusual wood pattern was cultivated especially in the Orient and in some parts of Italy (Tuscany, Florence).

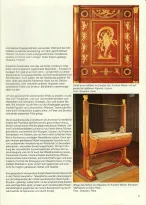

At first, the valuable burl wood, which was therefore cut to save as much volume as possible - veneers in today's sense did not yet exist - was used primarily to make small luxury objects such as jewelry boxes and carvings. Even later, in the design of larger surfaces, the lively burl wood usually remained only one decorative element among several other types of wood of different color and structure, which were combined pictorially.

To achieve the desired aesthetic effect, wood was sometimes dyed, and materials such as tortoise shell, ivory, pewter and other metals were also used. In marquetry, emphasis was placed on the reproduction of geometric figures, landscapes, plants, animals or portraits through the composition of selected parts that matched each other in color and texture.

The so expressive and strangely structured veneer surface challenges the viewer's imagination in a completely different way, similar to a picture of non-objective painting. Such veneer paintings remained mostly limited to relatively small areas, mainly for fillings, pilaster strips and friezes in combination with woods, which with their more plain wood image contrasted with the restless grain surface. However, surviving furniture from past eras also bears witness to extensive processing of burl wood into particularly decorative, valuable furnishing stitches. With the invention of modern veneering machines, veneer production and with it furniture making experienced revolutionary impulses. Today, traditional knowledge, newly acquired knowledge, valuable experience and modern technology allow the production of burl veneers on an industrial scale in a variety and quality previously unknown and also not thought possible.

Burl wood is used separately as solid wood in pipe manufacturing. Tobacco pipes are predominantly made from the burl of the Mediterranean tree heath - bruyére - whereby not only the appealing exterior plays an important role, but also the special resistance to the hard stress caused by changing temperatures and by impact.

Origin and characteristics of burl

Burl wood is the term used to describe logs or parts of logs whose wood appearance deviates in a certain way from the appearance characteristic of a wood species due to its structure. Burl woods have different growth forms, depending on the wood species, climate and soil conditions. However, the expert can already deduce a more or less pronounced grain formation from the stem shape and other typical criteria.

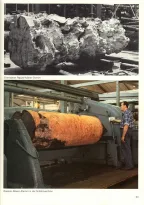

Three typical burl growth forms are shown on page 6. Although the photos all show Californian walnut (Juglans regia grafted on Juglans californica), the growth form designations are basically equally valid for all other burl woods. Burl growth is a freak of nature. Therefore, it goes without saying that even within a stem burl or root burl there are growth variations and thus mixed forms. However, not every irregular growth, such as the goitrous thickenings in constrictions or the bulbous overgrowth of branches and wounds, is a burl growth. True burl structures result from an annually recurring cluster of shoot attachments that remain in the emergence stage. This is indicated by the radial direction of their growth in the stem cross-section, the roundish structures in the tangential section, and the sometimes well-developed pith-like centers of the shoot attachments known as burls.

Since the growth stimulus for these structures persists over a large area for many years and only in isolated cases leads to small, leafy shoots, these structures, which are continuously renewed but do not develop beyond the stage of a "base," are also compared with the horticultural concept of so-called sleeping eyes. The question of why and how such a mass development of closely spaced shoots, which finally leads to maser growth, has often been asked, but without finding a complete answer and experimental confirmation. Thus, in addition to a possible predisposition, permanent stimuli in the cambium that influence growth, such as heat or constant mechanical damage, are considered a possible cause. The reason for this assumption is based on observations according to which constant browsing by animals on trees bordering on pasture, as in the case of ash, poplar and elm, and the felling of branches and brushwood for use as firewood, as happens in part in France, the most important country of origin of these woods, contribute to the development of burl growth. Fires, as in the case of North African thuja, makamong and padouk, and interventions by grafting in the case of Californian walnut woods, are also frequently associated with burl formation. Here it is quite possible that the above-mentioned injuries can lead to the tree becoming infected with growth-influencing bacteria or viruses. However, the connection seems to be assured only in the case of the emergence of Thuja burl, where the exposure to heat by fire has long been known to be a prerequisite stimulating burl growth. A direct connection can also be assumed in the case of the walnut tree, in which an irregular growth of the trunk (cluster) is more frequently observed after head grafting and the formation of burls after grafting at the root neck. An idea of how burl patterns are formed and which cutting direction to choose when processing can also be obtained by looking at a cut open unprocessed burl block (page 8): Initially, the color and structure of the wood in the inner parts of the log correspond to the normal picture typical for the respective wood species; it exhibits neither the gloss effects nor light-dark shading characteristic of burl growth. The first signs of grain development can be observed in the direction of the trunk exterior, when radially directed and outwardly expanding fan-shaped structures appear on the cross-section of the trunk, which essentially emerge through a different pore pattern (Fig. page 14, bottom right).

These structures resemble, as already on tangential cut surfaces, in a striking way beginning fine branch attachments. These radially directed structures can increase outwardly in such a way that the outer sections of the log are formed only from them. Finally, on the outer surfaces of the unprocessed burl woods, the grain structures, which appear band-like in radial section, radiating in cross-section, and roundish in tangential section, run out in small humped or truncated conical to thorn-like attachments, which are usually covered by a strongly barked and rough bark (Figures pages 8 and 9). Thus, all cutting directions can be identified, as the burl growth is not any irregular, wild undirected structures, but deviations of certain shape. For this reason, burl growth often develops similar, more rounded growth forms of the stem part in question, the so-called burls. Burl growth can be identified by single large or numerous smaller bulbous attachments on the mantle of the stem. In some species, strong bulges are also formed running around the trunk, which, when cut to length, often result in a spherical shape, can reach diameters of more than one meter, and can weigh several tons. The latter globular shape is formed predominantly at the base of the trunk (rootstock) and can be observed in walnut, myrtle, maple, madrona, and padouk; burls of redwood and African thuja are similar but have a more irregular appearance, while burl growth in ash, poplar, and elm can be identified by bead-like deformation along the entire length of the trunk (Figures page 13 bottom right, page 14 bottom left, page 17 bottom right, page 18 bottom left, page 20 bottom left).

A monopole of nature

Since the biological relationships, as mentioned above, have not yet been finally clarified, a programmed production of burls and burl strains has so far remained a pipe dream. News about forestry measures in Japan to achieve particularly structured woods concern the production of logs with coarse-grained or fine-grained or fluted outer surfaces, i.e., with vertical grooves. In this process, long bamboo sticks are pressed firmly in the axial direction onto the trunks of young trees of the Japanese cryptomeria in order to produce fluting at these points by inhibiting growth. This is a method comparable to the naturally occurring constrictions caused by lianas. However, the result of this growth interference has nothing to do with burl growth. These biologically produced artificial products are used only in Japan in house construction as visible pillars, which are given a special appearance by a uniformly tension-backed surface.

Accordingly, the burl veneers produced today all come from woods with special growth forms, the creation of which still reveals something of the unfathomable randomness of nature.

The huge tubers and burls depicted in the photographs certainly represent rather unique one-off specimens found only every -ty years, and in this respect this article represents a rare source of images of one-off rarities from a long period of the second half of the 20th century.

The article of the eminent scientist, researcher and author Helmut Gottwald (1918 -2008) represents an important source on the subject of measles growth, the contents of which are unique in this concentration precisely because of the unique images. Here are excerpts from the text by Prof. Gottwald as well as some pictures of sensational rarities from Danzer Veneers.

Burl growth: a picturesque freak of nature! by Helmut Gottwald, Reinbek

Burl woods are among the most decorative woods on earth due to their structural appearance. There are not many of them, because their species and growth areas are limited, and only a limited number are on the market. They come from deciduous and coniferous trees, whose wood, caused by a budding occurring in a clustered form, has extraordinary structures.

The following article provides an overview of the most important species as well as the origin and characteristics of burl growth.

Since the production of furniture and parts for interior finishing has increasingly been based not only on technical requirements but also on appearance, the choice of wood species has increasingly been determined by the appearance of the wood. Already in historical times it was the desire of the privileged classes to own beautiful or fancy pieces of furniture, which, in addition to their usefulness, also pleased by the beauty of the material. This is how furniture came into being, which, due to a deliberately sought after imagery of wood and the wealth of ideas in the composition of material and form, are among the essential elements in the development of our living culture.

The decisive aesthetic and economic aspects of using the material wood in all its natural diversity also led to the use of unusual and often only sporadically occurring growth forms of generally known wood species, such as bar growth in maple or the 'pyramid' and 'pommelé' structures in mahogany woods, for an additional expansion of the aesthetic expressiveness of the wood. It is understandable that such individually structured woods for special pieces of furniture and decorative room furnishings were sought after at all times and still enjoy high esteem today across all fashions.

One of the most striking deviations from the normal wood structure is the grain growth: it is a wood with numerous fine, swirly structures.

One of the most striking deviations from the normal structure of wood is probably burl growth: it is a conspicuous grain pattern with numerous fine, swirly structures, caused by an accumulation of buds or very fine knots over many years, the causes of which have not yet been definitively clarified. This picturesque whim of nature has always aroused the special interest of wood processors. Thus, already the Roman writer Pliny the Elder, who dealt with nature in detail in his writings in the middle of the first century AD, gave a description of burl growth. Already in his time Thuja burl was used for decorative design of furniture and utensils. During the Middle Ages, the use of thin-cut wood with a mostly unusual wood pattern was cultivated especially in the Orient and in some parts of Italy (Tuscany, Florence).

At first, the valuable burl wood, which was therefore cut to save as much volume as possible - veneers in today's sense did not yet exist - was used primarily to make small luxury objects such as jewelry boxes and carvings. Even later, in the design of larger surfaces, the lively burl wood usually remained only one decorative element among several other types of wood of different color and structure, which were combined pictorially.

To achieve the desired aesthetic effect, wood was sometimes dyed, and materials such as tortoise shell, ivory, pewter and other metals were also used. In marquetry, emphasis was placed on the reproduction of geometric figures, landscapes, plants, animals or portraits through the composition of selected parts that matched each other in color and texture.

The so expressive and strangely structured veneer surface challenges the viewer's imagination in a completely different way, similar to a picture of non-objective painting. Such veneer paintings remained mostly limited to relatively small areas, mainly for fillings, pilaster strips and friezes in combination with woods, which with their more plain wood image contrasted with the restless grain surface. However, surviving furniture from past eras also bears witness to extensive processing of burl wood into particularly decorative, valuable furnishing stitches. With the invention of modern veneering machines, veneer production and with it furniture making experienced revolutionary impulses. Today, traditional knowledge, newly acquired knowledge, valuable experience and modern technology allow the production of burl veneers on an industrial scale in a variety and quality previously unknown and also not thought possible.

Burl wood is used separately as solid wood in pipe manufacturing. Tobacco pipes are predominantly made from the burl of the Mediterranean tree heath - bruyére - whereby not only the appealing exterior plays an important role, but also the special resistance to the hard stress caused by changing temperatures and by impact.

Origin and characteristics of burl

Burl wood is the term used to describe logs or parts of logs whose wood appearance deviates in a certain way from the appearance characteristic of a wood species due to its structure. Burl woods have different growth forms, depending on the wood species, climate and soil conditions. However, the expert can already deduce a more or less pronounced grain formation from the stem shape and other typical criteria.

Three typical burl growth forms are shown on page 6. Although the photos all show Californian walnut (Juglans regia grafted on Juglans californica), the growth form designations are basically equally valid for all other burl woods. Burl growth is a freak of nature. Therefore, it goes without saying that even within a stem burl or root burl there are growth variations and thus mixed forms. However, not every irregular growth, such as the goitrous thickenings in constrictions or the bulbous overgrowth of branches and wounds, is a burl growth. True burl structures result from an annually recurring cluster of shoot attachments that remain in the emergence stage. This is indicated by the radial direction of their growth in the stem cross-section, the roundish structures in the tangential section, and the sometimes well-developed pith-like centers of the shoot attachments known as burls.

Since the growth stimulus for these structures persists over a large area for many years and only in isolated cases leads to small, leafy shoots, these structures, which are continuously renewed but do not develop beyond the stage of a "base," are also compared with the horticultural concept of so-called sleeping eyes. The question of why and how such a mass development of closely spaced shoots, which finally leads to maser growth, has often been asked, but without finding a complete answer and experimental confirmation. Thus, in addition to a possible predisposition, permanent stimuli in the cambium that influence growth, such as heat or constant mechanical damage, are considered a possible cause. The reason for this assumption is based on observations according to which constant browsing by animals on trees bordering on pasture, as in the case of ash, poplar and elm, and the felling of branches and brushwood for use as firewood, as happens in part in France, the most important country of origin of these woods, contribute to the development of burl growth. Fires, as in the case of North African thuja, makamong and padouk, and interventions by grafting in the case of Californian walnut woods, are also frequently associated with burl formation. Here it is quite possible that the above-mentioned injuries can lead to the tree becoming infected with growth-influencing bacteria or viruses. However, the connection seems to be assured only in the case of the emergence of Thuja burl, where the exposure to heat by fire has long been known to be a prerequisite stimulating burl growth. A direct connection can also be assumed in the case of the walnut tree, in which an irregular growth of the trunk (cluster) is more frequently observed after head grafting and the formation of burls after grafting at the root neck. An idea of how burl patterns are formed and which cutting direction to choose when processing can also be obtained by looking at a cut open unprocessed burl block (page 8): Initially, the color and structure of the wood in the inner parts of the log correspond to the normal picture typical for the respective wood species; it exhibits neither the gloss effects nor light-dark shading characteristic of burl growth. The first signs of grain development can be observed in the direction of the trunk exterior, when radially directed and outwardly expanding fan-shaped structures appear on the cross-section of the trunk, which essentially emerge through a different pore pattern (Fig. page 14, bottom right).

These structures resemble, as already on tangential cut surfaces, in a striking way beginning fine branch attachments. These radially directed structures can increase outwardly in such a way that the outer sections of the log are formed only from them. Finally, on the outer surfaces of the unprocessed burl woods, the grain structures, which appear band-like in radial section, radiating in cross-section, and roundish in tangential section, run out in small humped or truncated conical to thorn-like attachments, which are usually covered by a strongly barked and rough bark (Figures pages 8 and 9). Thus, all cutting directions can be identified, as the burl growth is not any irregular, wild undirected structures, but deviations of certain shape. For this reason, burl growth often develops similar, more rounded growth forms of the stem part in question, the so-called burls. Burl growth can be identified by single large or numerous smaller bulbous attachments on the mantle of the stem. In some species, strong bulges are also formed running around the trunk, which, when cut to length, often result in a spherical shape, can reach diameters of more than one meter, and can weigh several tons. The latter globular shape is formed predominantly at the base of the trunk (rootstock) and can be observed in walnut, myrtle, maple, madrona, and padouk; burls of redwood and African thuja are similar but have a more irregular appearance, while burl growth in ash, poplar, and elm can be identified by bead-like deformation along the entire length of the trunk (Figures page 13 bottom right, page 14 bottom left, page 17 bottom right, page 18 bottom left, page 20 bottom left).

A monopole of nature

Since the biological relationships, as mentioned above, have not yet been finally clarified, a programmed production of burls and burl strains has so far remained a pipe dream. News about forestry measures in Japan to achieve particularly structured woods concern the production of logs with coarse-grained or fine-grained or fluted outer surfaces, i.e., with vertical grooves. In this process, long bamboo sticks are pressed firmly in the axial direction onto the trunks of young trees of the Japanese cryptomeria in order to produce fluting at these points by inhibiting growth. This is a method comparable to the naturally occurring constrictions caused by lianas. However, the result of this growth interference has nothing to do with burl growth. These biologically produced artificial products are used only in Japan in house construction as visible pillars, which are given a special appearance by a uniformly tension-backed surface.

Accordingly, the burl veneers produced today all come from woods with special growth forms, the creation of which still reveals something of the unfathomable randomness of nature.